- Home

- Bella Mackie

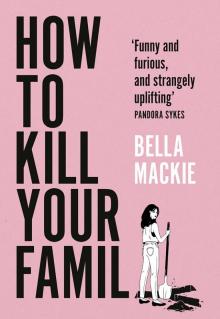

How to Kill Your Family Page 5

How to Kill Your Family Read online

Page 5

Two weeks later, she bumped into him outside another club. It was raining, and she was huddled in the queue, holding her coat aloft as she jostled with the other hopefuls trying to gain entry into the exclusive nightspot, all desperate to experience the decadence promised within, or at the very least get out of the rain. As we sat there on the sofa bed, my mother looked into the distance and her voice grew soft, as she described how a blacked-out sports car pulled up outside the club, splashing the pathetic crowd as it screeched to a stop. By the time she told me about my father, he had already treated her with a cruelty that makes my stomach burn, and yet she spoke about him with affection in her voice, and perhaps even awe. ‘He got out of that car, and threw his key to the valet who was standing by. I only noticed him because of the awful noise from the car. And when I saw him throw the keys … bouf … I thought it was a horribly arrogant move, to park a car in the middle of the road like that.’

She looked away, she insisted, as the bouncers unclipped the red velvet ropes to usher him inside, and the crowd pushed forward, angry that they were still stuck in the cold. And then a hand beckoned her towards the rope. A stern-looking woman with a clipboard nodded rapidly as if to say ‘yes, you’, and Marie weaved through the throng, and presented herself to the doormen. She was directed inside, she explained, and wasn’t about to question it, even as the people behind her grumbled and booed. As she got to the bottom of the stairs, she was met by him, leaning against the wall, arms crossed, smirking. I’ve seen that smirk many times in the press. It’s almost his signature expression. A powerful combination of arrogance and charm. An infuriating combination too, since you quickly find that with men like that, the arrogance always overcomes the charm and yet by then it’s too late, for the initial mix is intoxicating and hard to forget.

‘So you don’t want my champagne, but you’ll accept my hospitality?’ he said, looking her up and down. Honestly, I still think poorly of her for not turning around and walking away right then and there. Even aged nine, when she relayed their initial meeting to me, I remember thinking that this was a truly pathetic opener. If I’d ever imagined that my father might have been some mythical figure who we lost to a heroic act of bravery, this is the moment when that unspoken assumption died. My father was a cheesy charlatan in an expensive suit, and my mother ate it up.

I assume she played it cool at first, batting him away with some witheringly French put-down, but even if she did, it still counted for nothing. By the next day, he’d found out her address and turned up in a soft-top filled with flowers. Her flat-mates woke her up screaming with laughter, as Helene told me much later, teasing her about the British man in the flat cap who was tooting the horn and holding up traffic. A week later, he flew her to Venice on a private jet, taking her to St Mark’s Square for cocktails (honestly, how tacky), and telling her that he loved her. The extravagant displays of affection continued over the next few months, as they would go out for dinner, to the nightclubs they both loved, to walk in Hyde Park on sunny Monday mornings. Her barriers were demolished, no longer was she cautious and dismissive of London men and their intentions. Marie stopped going to castings as much, preferring to be available if he happened to call. And he did, frequently. But only between Monday to Friday, and he rarely stayed the night with her, crying off with work, or explanations about his elderly mother and her need for him to stay sometimes.

Did your eyes just roll back inside your head so hard it made you wince? Well yes. We can dwell on my mother’s stupid decision to place her faith in a man who wore large buckled belts and enjoyed the music of Dire Straits, or we can move on. I don’t have enough time in this place to unpack the manipulation on his end or the naivety on hers. Obviously, my father was already spoken for. Not just spoken for, he was married with a baby, and he lived in a house high on a hill in North London which had several live-in staff, two pedigree dogs, a wine cellar, swimming pool, and several acres of grounds. He wasn’t just committed, he was embedded.

This bit of the story was left out when I was first told about him. I don’t blame Marie for glossing over some of the more delicate details I probably wouldn’t have fully understood anyway. Instead, my mother attempted to explain why my father never came to see me, never sent me a birthday present, never turned up at parents’ evening. Stroking my arm, Marie told me that he was involved in big and important business deals which affected the lives of thousands of people, and that’s why he couldn’t see us. He flew around the world, she said. He loved us both very much, and when the time was right, we’d all be together, but right now, we had to let him work hard and prepare for the time when we could live as a family. Did she believe it herself? I’ve often wondered. Was my smart, kind mother really so, to be blunt, stupid? Maybe. My sex is so often disappointing – I remember once reading about a woman who married a man who convinced her that he was a spy. He persuaded her to sign over her life savings to him, to the tune of £130,000, saying that he was undercover and needed it to tide him over until his handlers could safely make contact. She’d never asked for proof, so desperate was she for this ridiculous charade of a love affair to be real. And to compound her humiliation, she’d willingly posed for photos in a weekly magazine and told her story, looking downtrodden and sad. Was I supposed to feel sorry for this person, a grown-up who dreamt of fairy-tale romance, and didn’t question why this man whisked her, a woman in her fifties (who looked every inch of it), off her feet? Marie was a cut above this woman and those like her, but she obviously still had the capacity for similar delusion.

For all the ridiculous promises that Marie made to me about my father and our eventual life together, she was wise enough to only tell me selective information about him. Enough to stop my questions, not giving me anything too concrete. But she did make the mistake of pointing out his house to me after a trip to Hampstead Heath a few months later. We got lost in a wooded area, and it started to rain. My mother grabbed my hand and marched me up a hill, attempting to find a route to the main road where we might get a bus. But when we finally got to the bus stop, she briskly carried on, as I grumbled and pulled my anorak tightly around me. Despite the torrential skies, we walked another ten minutes down a long private road, until she slowed down and finally stopped.

We stood in front of a house and Marie stared up at it silently for a moment, until I yanked on her hand impatiently. I say we were looking at a house, but the enormous iron gates with security cameras attached deliberately obscured most of the actual property. We lived in an attic room on a main road. I had never imagined that a house could be so important it would have to be hidden from view. Without looking down at me, my mother gestured towards the gates, almost reverentially. ‘This is your father’s house, Grace,’ she said, still not looking at me. I didn’t know what to say. I felt uncomfortable lingering in front of this grand place, drenched to my skin. Marie must have noticed that I was slowly moving backwards, trying to encourage her to head to the safety of the bus stop and home, so she smiled brightly. ‘Such a shame your father isn’t in today, but isn’t it lovely, Grace? One day you will have your own bedroom there!’ I nodded, not knowing what else to do. She took my hand, and we turned around, and headed away, back down the hill to our home. We never mentioned that trip again. But I thought about that bedroom she’d promised would be mine many times growing up. I imagined it, with pink wallpaper and a big double bed, and maybe even a wardrobe full of new clothes, but even when I burrowed down deep into this rabbit hole, I knew that Marie had been lying, and that there would never be a bedroom behind those grand gates for me. And even then, I remember understanding so clearly, that something very wrong had been done to Marie and me.

So that’s my dad. Not the one I’d have picked had I been consulted, but there we are. Some people have fathers who beat them, some have fathers who wear Crocs. We all have our crosses to bear. I haven’t told you much about his personality or his background, have I? That’ll come. But if you really want to understand why I did what I d

id, I have to go back to my childhood again first. Hopefully it won’t sound too self-indulgent, but even if it does, well, it’s my story. And I’m currently lying on a bunk bed in a cell which smells like a potent mix of sadness and urine, so I’ll take any excuse to escape into my memories.

Here are some early memories: Marie not having enough money for food, electricity, and on one grim occasion, for sanitary products. Getting up at 6 a.m. so that Marie could get to work on time, where I would sit in the backroom of the coffee shop and do my homework. Seeing my mother so tired that she looked yellow and hollowed out day after day. Being cold all through winter because we only used the heating at the beginning of the month when Marie got paid. Being cold instils a raw fear in me to this day. I paid to have extra radiators installed in my flat as a grown-up, much to the bemusement of my landlord, and forked out an obscene amount of money for a, in hindsight, fairly hideous fur throw to blanket my bed, because I needed certainty that I wouldn’t wake up shivering, as I had done so often as a child. Fur might be unethical but truly, it feels wonderful next to the naked body.

Marie dealt with our lack of money and support as best she could. Her parents, disapproving of her life choices, as they put it, gave her nothing. Hortense met us for lunch once, on one of her trips to London on which I can only assume she terrorised shop girls and made waiters cry for fun. My mother put me in my best outfit, which consisted of an itchy jumper she’d bought for me at M&S one Christmas (which I hated, but she was proud of, because it was real wool and had a pie-crust collar), and corduroy trousers, which pinched at the stomach and had belonged to another child at my primary school, before being handed on to me. My grandmother said hello to me, then promptly turned to my mother and spoke in French for the rest of the meeting. Marie would answer in English, which served only to make Hortense even more determined. As we left the restaurant, Hortense bent down, pulled my jumper sleeve towards her face and sniffed. She said something to my mother as she gestured back at me, and my mother’s eyes sprung with tears. That was the last time I ever saw the old witch. When Marie died, she sent me a letter, which I didn’t open, opting instead to flush it, piece by piece, down the toilet at Helene’s house. She must be dead by now, but I hope she isn’t. I hope she sees the news reports about me. I hope she and her repressed old husband got doorstepped by scummy tabloid journalists during my trial, and I pray that their neighbours view them with suspicion, or worse – faux sympathy.

So we were poor, and Marie had nobody, apart from Helene. Bea, her only other real friend, had fled back to France after a doomed love affair and a mean model agent who suggested in so many words that she should try to develop an eating disorder if she wanted to make any money. Occasionally, my mother would write long letters late at night, as I pretended to be asleep. She’d sit at the kitchen table, tearing up pieces of paper, and starting again and again. In the morning, the letters would be propped up on the table, ready to take to the postbox. I didn’t recognise the name until I was older, when I saw a discarded attempt in the bin and fished it out.

My darling, I know we cannot meet again, and I have always respected your decision. You know how much I loved you, and that I would never do anything to hurt you or jeopardise your family. But Grace is growing up, and I wish so much for you to know her – just a little. I do not ask for money, or expect that we can ever experience the closeness we once revelled in. But she needs her father! Sometimes she tilts her head and gives me a little smirk, and she looks just like you, which inflicts such a mixture of pride and pain you could never imagine. Perhaps you could come and meet us one Sunday at the park in Highgate, just for an hour? Please write back to me, I never know if you are reading these letters.

From this letter, I learnt three very important things. First, that snooping will almost always pay off. Second, that my father was married and wanted nothing to do with me, despite Marie’s attempts to spin me a different story. And third, and most importantly, I found out the name of the philanderer who broke my mother’s heart and left us to live in misery. I already knew his name, it turned out. Most people do. My father is Simon Artemis. And he is one of the richest men in the world. I should say was, back when he was still alive.

That was the bell. I have to go and do laundry. Endless greying sheets to wash and fold. The glamour is sometimes too much to bear.

CHAPTER FOUR

My younger years were not like something out of one of those terrible books you see in airport bookshops, usually called something like ‘Daddy Don’t’, which might be a story of unimaginable suffering, but only sell because people like to read about other people’s misery and feel good about themselves afterwards, simply for feeling the merest shred of sympathy or horror. ‘I read this and cried my eyes out, such a sad story :(’ is the usual review on some online mum book club. Oh, you read about child abuse and constant trauma and found that upsetting did you, Kate1982? (Kate just sounds like the name of someone who’d frequent a site like that.) So glad you could tell us all how it affected you.

Anyway, my childhood (the part Marie was alive for anyway) had some good moments. I was very loved, and I knew it – even though it all came from just one person. Mothers are adept at providing love from all angles, so much so that you often don’t realise you’re missing out on love from other people until much later in life. Marie took the brunt of the hardship and hid it well from me. Of course I knew she was struggling, children always do, don’t they? But children are also astonishingly selfish, and as long as she successfully managed to paper over most of the cracks, I was more than happy to go along with it. My mother would save up her wages – from her job as a barista at a coffee shop in the Angel where hot drinks were at least £3 and cake was made without flour for those women who’d recently discovered gluten intolerance, and from her cleaning gig which took her to the homes of the ladies up in Highgate who probably didn’t eat cake at all. Every three months she would have just enough to take me on a ‘magical mystery tour’, which just meant a trip to the Cutty Sark, or a Tube ride down to Selfridges to see the Christmas lights. Once she took me to the fair up on Hampstead Heath, where I ate candy floss for the first time and won a fish during a game of hoops. We put the fish in a vase on our kitchen table and called it RIP, which I thought was funny since fairground fish never live very long. Marie thought it was mean, and nurtured that fish, cleaning out its home every week and adding in some green plants and a desultory rock. I lost interest in that fish, but under her early care, RIP ended up living for ten years. He outlived my mother.

Marie and I struggled on. I went to a nice primary school just off Seven Sisters where I made precisely one friend, a boy named Jimmy, whose family lived in a very large house with an excessive number of rugs and cushions and books stacked from floor to ceiling in every room. His mother was a therapist, and his father was a GP, and they easily could have sent their son to a prep school not situated next door to a pawn shop which did a nice side hustle in hard drugs. But they had a big Labour poster in their window and carried a huge amount of liberal guilt about their good fortune, and Jimmy’s education was one of the ways they squared it. Jimmy is still in my life. In fact, our relationship has matured somewhat in recent times, I guess you could say.

We might have gone on like this, Marie and me. I went to secondary school down the road (with Jimmy initially, who was mercilessly teased for being posh in Year 7 and so was sent off to a private day school which had goats and did a lot of art – another tortured compromise made by his parents), and I made a few more friends. Perhaps if we’d had longer, Marie might have got a better job, and who knows, maybe met a nice man to take some of her burdens. I might have made it to university, and later earned enough to look after my mother, buy her a flat, get her a car. But if that had been our fate, then I wouldn’t be here, writing this, waiting for Kelly to burst into our cell and try to lure me into a conversation about her brassy DIY highlights. Instead, Marie got slower, greyer, and slept more, to the point where

I was getting up for school and leaving her in bed. She lost a cleaning job because she didn’t wake up until 11 a.m. one morning, and some starch-faced witch in a house which had six bathrooms and no soul fired her by text at 11.30 a.m. Her back ached, she said one night, chatting to Helene on the sofa as I dozed in bed. Helene urged her to see the doctor, but she dismissed it. ‘When have I not had aches and pains since we’ve been in this cold damp country?’ she laughed.

Who knows how bad she really felt? Certainly not me. Kids are self-absorbed and parents are supposed to be invincible. That’s the deal. But Marie broke it. Two months later, she took me on holiday for the first time, to Cornwall. We stayed in a caravan park on a cliff overlooking the vast sea, and we walked along coastal paths and I ate a lot of ice cream. Marie drank wine on the doorstep of our van as I lay on the grass and asked her questions about her childhood in France, about how I could train to be a photographer when I grew up, about whether I would ever like boys in the way that grown-ups did if they were all as immature as the ones in my class. She laughed at that one. She laughed a lot that holiday.

How to Kill Your Family

How to Kill Your Family